I’m not going to claim that I’m an official historian of Nihonshu, but I will attempt to give an honest collective of hard opinions that have been agreed upon. You can already guess that the origins go back to somewhere before Christ but the exact records of how it was developed have been blurred.

However, a rough version of an alcoholic drink brewed from rice has been traced back to China. It was the result of the wide cultivation of rice. It can be concluded, however, that harvesting rice in the rice patties already created warm humid conditions.

Without refrigeration, that would spawn a happy environment for wild yeast to start fermentation. As with many developments in the past, this came about as a happy accident. When rice was introduced to Japan in the Nara Period (710-794), This is where the Japanese can lay claim to being the pioneers of the Nihonshu we know as of today.

Japan advanced and refined the art brewing process of Nihonsu!

NIHONSHU PROCESS

(IMAGE FROM SLIDE PLAYER)

🍚 Rice Polishing

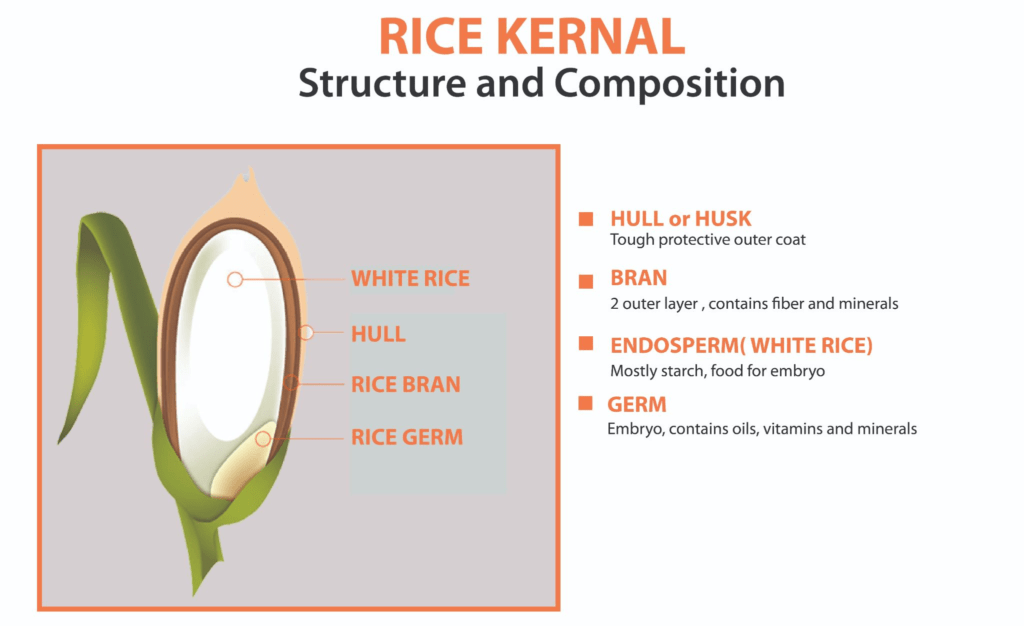

When rice is harvested, it has all of its protein components intact. Its outer layers are pigmented, composed of bran fibers, germ oils, starch, and sugars; almost like layers of clothes you want to shed off on a hot day. It’s a buffet of flavors. However, the goal for Nihonshu is to craft an alcoholic beverage from its natural pure essence.

When the Nihonshu selected rice initially arrives at the brewery, the first step is to polish down the rice to remove all the protein layers which will expose the grain’s starchy core. It’s basically naked and ready for the heat.

There are two schools that will reference the process either way for EACH grain… polished or milled.

I like to say POLISHED because the grains are so eloquently handled. The more the grain is polished, it will result in a finer, transparent style. The percentage to which the rice is polished is called “SEIMAIBUAI”. This always refers to the amount of rice remaining. After which, the grains are ready to be washed.

(IMAGE FROM JAPANESE SAKE CAMPUS)

🍶. Rice Laundry

The brewers call it “rice washing”. I like to call it “rice laundry”. After the rice is polished, it’s dusty with all the milled rice flour, called “NUKA”. This must be washed off in order to begin the next step, which is introducing moisture to each grain. There’s no Whirlpool washing machine with smart settings for this. It’s all done by hand and the laundry timing is specific, right down to the second. The 3rd step is teabagging. Oh My!

🕙 Steeping The Rice

For me, this step is like steeping tea. The grains are being softened to begin extracting their flavors. This prepares the rice for steaming. This step continues to introduce moisture into the grain.” Remember, more moisture creates a party for yeast when they arrive. No time for a lunch break because there is a timer on this too.

🕝 Steaming Rice

No rice cooker is set as a timer for this step. Next on the schedule is rice steaming. Rice is spread out in the steamer and steamed from below. Finally!, an hour gap for this step it takes more or less an hour, depending on the rice strain. The heat and moisture of the steam change the configuration of the starch in the grain.

I like to compare it to practicing Bikram Yoga. Between the hot environment and steam emanating from your pores, it restructures your body. The same applies to the easier breakdown of starch for the rice grains. After it is freshly steamed, the rice is then moved to the next step.

🕥 Making Mold

Called “Koji-kin”, it is a mold. Koji is rice that has been infected with mold, which sounds like a bad date! However, freshly steamed rice is moved to the koji-making room, which is usually either wood or metal walls and is stiflingly hot.

The rice is spread out on long tables and allowed to dry out briefly on the outside of each grain. The objective is to have each grain moist inside and dry on the outside. This boosts the koji mold to work hard in search of water within each grain to prepare the fermentation. After the rice is groomed in the koji room, the koji mold powder is dusted over the grains. And after roughly four days, the mold has fully blanketed each grain thereby creating the Koji Rice. All the components are now ready to start fermentation for the next stage.

🕖 Fermentation Initiator

Next comes what is known as the shubo or moto, which equates to the fermentation /yeast starter. Yeast, water, steamed sake rice, and koji-rice are thrown into the pool together in a small tank. Of course in the modern world, we want everything like yesterday. There is a yeast starter method called Sokujo, that has the turbocharger of a Ferrari. It takes about 2 weeks to create this limited quantity of sake as opposed to a month or more for vintage methods. It’s used mostly by contemporary producers who are looking for the “Fight Club” of sake yeast cells. These are yeast cells that are super active that can craft sake in a short period of time. And we all know time is money. Those of you looking for traditional methods to forsake, read up on Kimoto, Yamahai, and Bodai-moto in the STYLES section.

🕑 The Monster Mash.

This is called Maromi. The groundwork has finally been laid, and I’m exhausted for these guys. In the main brewing tank, water, rice, koji-rice, and the fermentation starter are added to develop this mash; either at turbocharge or the slow mail method. Either way, the process is known as San-dan-Jikomi. I would hate to be appointed to be in charge to remember to add three additions of the mash of ingredients over a 4 days period. This process for the mixture is like adjusting to an arranged marriage with someone you never lived with.

The yeast and koji nest together daily without giving any room for unwanted wild child microorganisms to be created. After the third addition of rice; water, yeast, and koji, the mash is left to ferment for an additional 20-25 days.

🕢 A Pressing Issue

Once the sake is done brewing, the newly created alcohol needs to be separated from the unfermented rice solids left in the mash. There are several methods for pressing sake, but the most common is the automatic pressing machine known as a Yabuta. The main body of the machine is made up of metal frames stacked tightly together. The mash is poured into vertical pockets of these frames and pressure is applied from the side. The sake is forced out of the bottom and the fabric mesh lining the frames holds the rice solids behind. These rice solids are known as “kasu”. After pressing, the frames of the machine can be opened and the sake kasu peeled out. The raw sake at this stage is full strength, usually around 18% alcohol at this point and unpasteurized. The next step is to filter the Nihonshu, so it appears visually clean in your eyes.

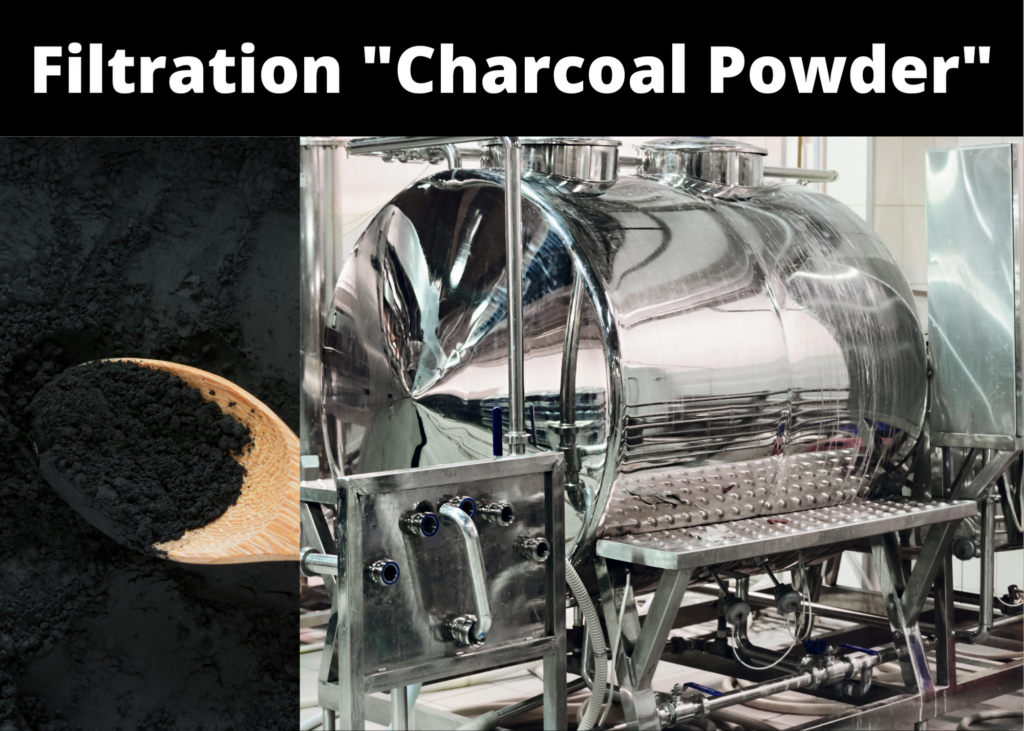

⏰ Filtration Chemistry

The Japanese pride themselves on delivering a product in pure form and Nihonshu is shared in this pride. After pressing, the fine particulate is removed by filtration using charcoal powder. Now we begin to see some vodka style-making characteristics.

Charcoal is porous and acts like a magnet to the particulates, dead yeast, enzymes, or any other remaining bits of starch. The charcoal powder and Nihonshu are mixed together and then run through a chambered filter lined with special filter paper. The result is a super clear NIhonshu, and will now go to Pasteur.

🐄 Pasteurization

Even though the Nihonshu looks clear to the naked eye even at 20/20 vision, MOST are pasteurized. (When you read on the STYLES further down, that will be clarified). This quickly heats the sake to around 150˚F.

The purpose of this heating is to put the yeasty enzymes in a permanent coma and to kill off any remaining bacteria. This makes the Nihonshu bottles you see on store shelves stable; free from anything growing inside.

Think of the milk you buy and on the label, it states ULTRA PASTEURIZED. This is to eliminate contamination of any bacteria. But because milk doesn’t contain alcohol, which acts as a preservative, dairy is usually ULTRA PASTEURIZED.

There are several methods to do pasteurization. One way is to run the sake through a pipe that is heated. ( I just got excited, is that a smoking pipe!?) Damn, no it’s not!. The Nihonshu circulates in the pipe until the desired temperature is reached. The other methods are used for your headache-inducing hot Nihonshu or lower quality versions. These include, the bottles showering under scorching conditions or drowning the bottles in hell water temperatures. After the crafted Nihonshu has been exposed to extreme heat, it needs to settle down and rest. The next step is storing it.

✌. Storage; Finding Peace

This stage of the brewing process forces the Nihonshu on average, to rest for 3 months to ½ year in a tank. It’s almost like sending it to therapy. Nihonshu, 99% of the time will not be stored in wooden barrels like wine or whiskey. However, there are some brewers that like to experiment and are beginning to age Nihonshu in barrels. Regardless, the much-needed vacation relieves it

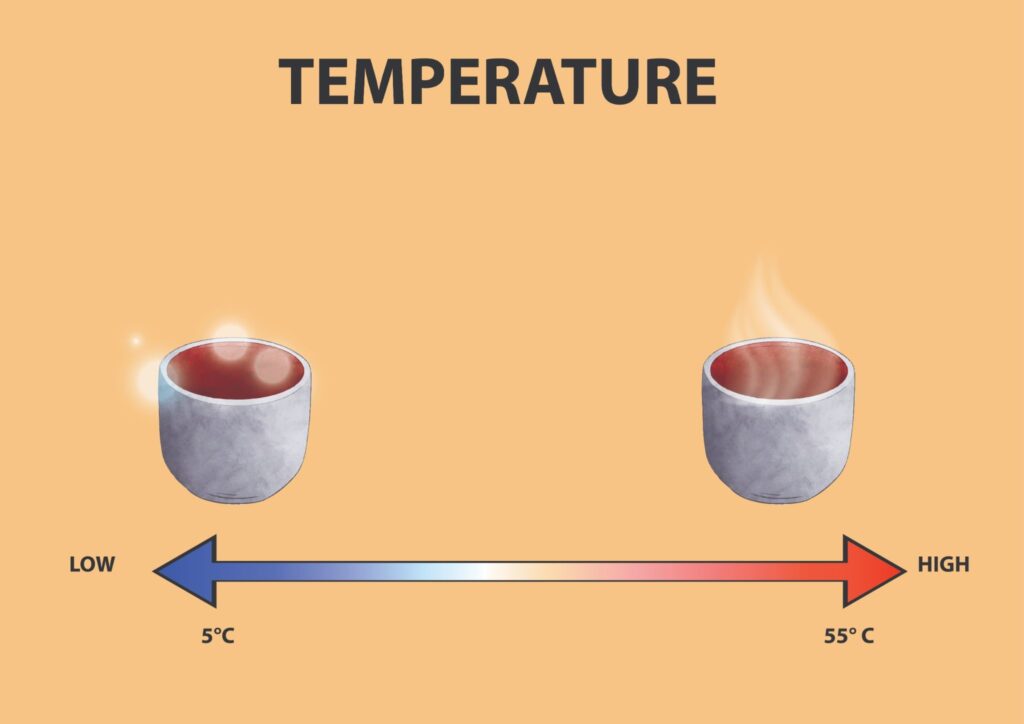

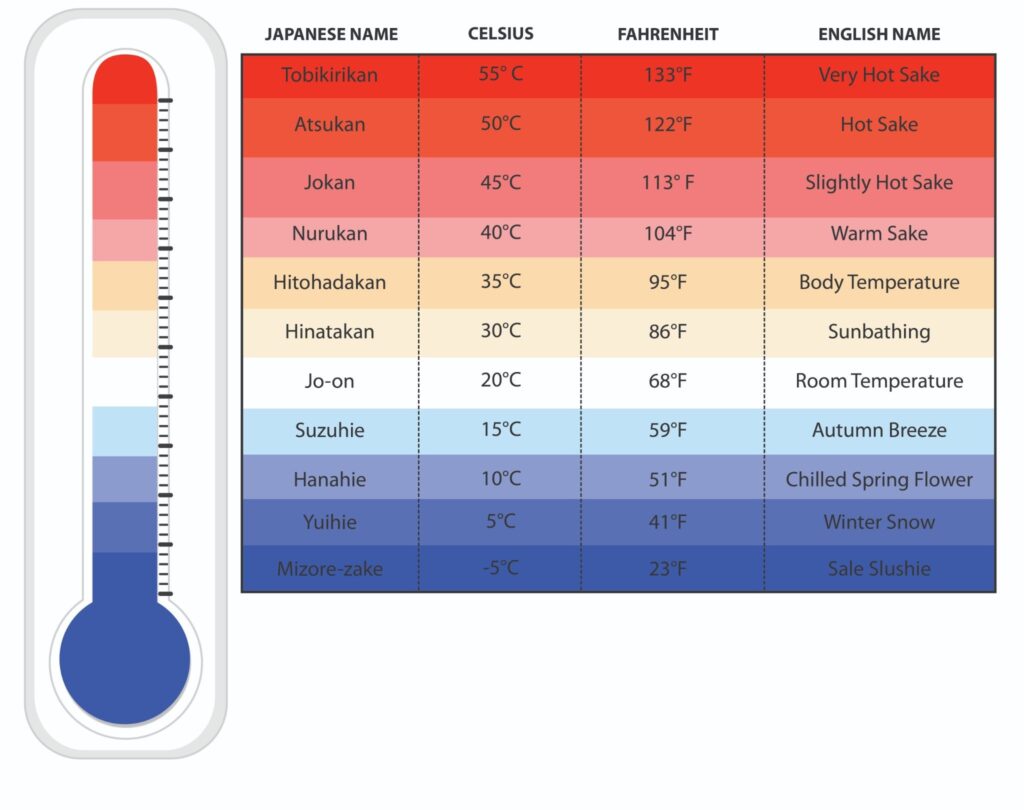

Depending on the style, Nihonshu can be savored in a wide range of temperatures.

🍼 Bottling

Nihonshu has usually pasteurized again and is diluted with pure water to bring the alcohol content to about 15%. Otherwise, you wouldn’t be able to get past the high octane and the nuances would just be muted. Then, machines fill and seal each bottle that’s still warm. When the bottles have cooled, they are then labeled. Wow!, now the Nihonshu is FINALLY ready for shipping.

TEMPERATURES

💣The misconception of Nihonshu is ONLY premium grades are served chilled and the cheapies are served hot. I’m going to clarify that rumor.

Temperatures ABSOLUTELY depend on the style. For example, Nihonshu with a full-body, earthy, and strong rice flavor is typically best expressed as slightly warm. Warming sake improves its umami flavors. If you don’t like an aggressive Nihonshu, don’t warm it. Similarly, Nihonshu that are very dry (Cho-karakuchi), and transparent can too benefit from some warmth. Conversely, fruity or floral Nihonshu is best expressed as slightly chilled.

SORRY THIS IS THE MORE ACCURATE ONE

STYLES

Finally, this will help you to understand what style of Nihonshu you are buying. Each one uses a different brewing method that will ultimately determine the style.

Many sites will tell you there are several main staples. Yes! There are subcategories, but there are only TWO main types that you will mostly see on labels: JUNMAI & GINGJO. Just remember this and you will know what Nihonshu to purchase with great pleasure and without confusion.

ANYTIME you see: 2 MAIN TYPES

Junmai: ( minimum 70% polish) it is ONLY made with purified water, rice and yeast; THAT IS IT! any term after that is a sub-style corresponding to it.

Gingo: (minimum 60% polish) Made with water, rice, yeast + a small portion of the brewer’s special distilled alcohol.

SUBCATEGORIES OF STYLES

The brewing process is what determines the next substyles of NIHONSHU. Rice polishing is the number one reason for its categorization and pricing. Here I described them and if I left anything out, please let me know in the comments.

Daiginjo – minimum 50% polishing. It is normally seen at a premium level because of its translucent flavor and aroma profile.

Honjozo – The most versatile of all Nihonshu. Polishing rates can be anywhere. It’s the complete opposite of his friend Junmai. Often polish at 70% or lower, along with the brewers “special” added distilled alcohol. I like to describe it as “The Most Interesting Nihonshu On Earth”. Served clean, easy, chilled, or warm!

Futshu – This Nihonshu is the “Stray Cat” of the streets. It represents 65% of Japan’s Nihonshu production. That is tremendous just thinking about it. This is the Nihonshu that is exported the most for your hangover drinking pleasure. By the way, you will never see the term label for the export market…Gee, I wonder why?

Nigori – Ever see Nihonshu that looks like, well, I’ll leave that to your imagination. This Nihonshu is not crystal bright but it looks like a cloudy mess. It contains particles of unfermented rice grains that are left intentionally at the filtration step.

It was once described as a sweet style panty-dropper for Bachelorette parties.

Today it’s a growing style that’s being increasingly made dry. Think about enjoying Nigori with a medium-rare prime rib steak at your favorite restaurant; the dry versions are masculine in texture and flavor.

Sparkling – A celebratory Nihonshu. This recent style is introducing itself to the bubble Industry like a samurai. I often wondered when the Japanese were going to enter this competitive market.

Champagne has another player on their heels- supported by the rest of the world’s sparkling wine producers. Initially, they were just a sweet version like Nigori, without a cloudy appearance and injected with carbonation. Today there is a serious movement by brewers in Japan who are making dry examples using the traditional methods of sparkling wine production.

Flavored – I describe this one as the “Club Pimp”. I almost want to say respectfully, it’s NOT Nihonshu. It’s a Nihonshu infused with anything the brewer desires, from fruits, herbs; you name it can be done. This popular category brings its own party to the table, where it can be mixed into a vast range of cocktails. It’s pure fun in a glass!

THE “WILD BUNCH” OF SUBCATEGORIES

90% of brewers use culture yeast, the other 10% allow wild yeast to begin the fermentations. These are singular, the crest of traditional styles. The number one reason culture yeast is mostly used is control. This means they can control as well as calculate the timing when the rice will be inoculated to begin fermentation. The other reason these cultured yeast are preferred is to leave nothing to chance.

While brewers want to determine the style of Nihonshu they want to craft by using cultured yeast, wild yeast have their own agenda. They can impart heavy rustic aromas that may be off-putting to unseasoned drinkers.

Also, it could tap into their capital because you never know when the wild yeast will start the fermentation. It could take up to a month, more or never. Polishing rates can be applied anywhere on the spectrum, with no minimum or maximum.

On the other hand, these are Nihonshu made with ancient methods. Poles are used to stir the mixture by hand which is a very labor-inducing process. Therefore they create wines that are excitingly unique, and at times very expensive. I love these Nihonshu. They are hard to come by and I encourage you to entertain your palate. You’ll be wildly amazed!

Kimoto – The most traditional of styles that will wake up your senses like an alarm. Kimoto Nihonshu is like throwing dice. They allow wild yeast roaming around the brewery to impregnate the rice for fermentation. When that will happen, no one knows, you could be sitting around for days. There is not much intervention. Either way, it’s not for everyone as they are deep, rich, and full.

Yamahai – This is the queen version of “King Kimoto” as it is similar to Kimoto. The only difference is the brewer still allows wild yeast but it also cheats a little by using lactic acid to start fermentation. The result is the same zoo flavors and aromas but is more tame. They have less acid with a creamy mouth-filling experience.

Nama – One word to describe this style is, unpasteurized. In other words, it’s like “raw anything” and needs to be refrigerated quickly. If you don’t, anything can show up in your glass. It’s very unstable like someone newly out of rehab. Even though these Nihonshu can be refreshing, they can have an immediate relapse.

Namachozo – I specified earlier in the “Pasteurization” step that most Nihonshu is pasteurized twice when bottled and just before shipping. Namachozo is one exception that is pasteurized ONCE before shipping, NOT at bottling.

I like to equate this to a method used in champagne where the wine is disgorged just before shipping. What results is a wine that is fresh, vivid, but needs to be maintained very chilled, consumed right away.

Namazume – While Namachozo omites the FIRST pasteurization, AND storing it unpasteurized, Namazume omites pasteurization altogether. This is the most unstable of all Nihonshu. Maybe carry a cooler and its sponsor on the way home for this one.

The natural wine movement is on fire at the moment and all those who are on a raw diet. They ought to be excited about Namazume Nihonshu.

Shiboritate – Although Nihonshu is not typically aged like wine, it’s usually allowed to mature for around six months or more while the flavors mellow out in inert tanks. However, Shiboritate goes directly from the presses into the bottles and out to market. Love it or hate it, Shiboritate’s sake tends to be wild and fruity. Sometimes drinkers even compare it to white wine, I like to compare it to Beaujolais Nouveau

Genshu – This is UNDILUTED Nihonshu. Don’t confuse it with Nigori. This means NO water was added before bottling to bring the alcohol level down to a coherent level. Has anyone heard of “Moonshine”? Most of these will never be on the export market, just for brewers who want to numb the pain after a hard-working day.

Muroka – Nihonshu usually goes through carbon filtration for attractive clarity and to balance its profile. Muroka translates as NOT FILTERED, and it eliminates this process to retain robust aromas and organic nuances.

ON A MISSION TO REVIVE INTERNAL MARKETS AND CAPTIVATE EXTERNAL MARKETS

Outside of Japan, sake is somewhat of a mystery, with its own terminology, styles, and drinking traditions. Once seen as a drink of their grandfathers, modern brewers are aggressively reviving it to make it more understandable and sexier to the new generation. It’s taking the global market by storm. Like many things in life, what was once old becomes new again.